Use JavaScript to Format Dates and Times on the Web

Clarifying meaning when displaying times and dates on web pages

This article describes a strategy for clarifying meaning when displaying times and dates on web pages. Confusion comes from omitting the time zone and when using an ambiguous digit order for the day and month.

This article describes

- Changing web pages after they are loaded,

- Using the DOM to manipulate text not delineated by mark-up, and

- Representing times and dates in web pages.

Imagine you’re looking at a web page presenting an activity log:

2/8/24 8:03 - Trim hedge

2/8/24 8:16 - Sweep drive

2/8/24 8:34 - Take out trash

Morning or evening? Summer or winter? British or American? Maybe I’m an American writing for a British audience. Maybe I’m a conscientious American writer who has diligently added ‘u’ characters after all the ‘o’ characters, but somehow just forgot to change the day/month order. Or is it month/day?

Let’s develop and implement a strategy for representing dates in a software interface where the language is English, but the audience is global. Here’s the strategy we’re going to use:

- The back-end dev is to write all event time stamps in the HTML in coordinated universal time using the W3C datetime format.1

- The front-end dev is going to automate the display of the time stamps to represent them unambiguously for each local reader.

The back-end dev

As backend devs, we’ll log events with compact ISO 8601 time stamps in

Ruby:

Time.now.utc.strftime('%FT%TZ')

Python:

import datetime

f"{datetime.datetime.utcnow().isoformat()}Z"

Java:

import java.time.*;

LocalDateTime.now(ZoneOffset.UTC) + "Z";

JavaScript:

new Date().toISOString();

and deliver HTML that looks something like this:

<pre>

2024-02-09T04:03:14Z - Trim hedge

2024-02-09T04:16:56Z - Sweep drive

2024-02-09T04:34:22Z - Take out trash

</pre>

The front-end dev

As front-end devs, we‘ll write JavaScript that scans the page text for these date stamps, and then replaces them with an unambiguous format customized for each site visitor.

Add an event listener

We start by inventing a name for the starting point of our solution,

localizeIsoStrings, and adding it to the page onload handler so it

runs when the page loads.

function localizeIsoStrings(event) {

}

window.addEventListener("load", localizeIsoStrings);

Plan the mark-up

We might grumble at the back-end dev for not wrapping each date stamp in

a span to make each one easy to locate, but we’ll roll with it. We

know that special items on the page need to be identified with semantic

mark-up for both presentation and accessibility. Since this whole

project is about date stamps, date stamps are clearly the special thing

here. When we’re done, we’ll have each date stamp properly wrapped in an

HTML span element like this:

<span

class="date localized-iso8601-string"

title="2024-02-08T20:03:14Z"

>Feb 8, 2024 at 08:03:14 PM PST</span>

Implement the mark-up plan

Here’s a function that returns our desired span mark-up:

function wrapIsoString(isoString, transformer) {

const span = document.createElement("span");

span.classList.add("date");

span.classList.add("localize-iso8601-string");

span.title = isoString;

span.textContent = transformer(isoString);

return span;

}

The function

- Creates a

spanelement. - Adds a

classattribute with two classes: one a generic “date” and one specific to the project, “localize-iso8601-string“. - Adds a

titleattribute with its value set to the original datetime format. In modern browsers, readers who hold their mouse pointer over an element with a title attribute for about two seconds will see the content of the title attribute appear in a pop-up. - Calls for a localized date stamp and adds it into the element’s text content, which will be immediately visible to visitors.

- Returns the

spanelement.

Transformation, first version

For the transformation, let’s start with an obvious solution:

new Date("2024-02-08T20:03:14Z").toLocaleString();

⬅︎ "2/8/2024, 12:03:14 PM"

Then wrap that in a function so we can reference it in our program:

function localDateString(dateTime) {

return new Date(dateTime).toLocaleString();

}

This function

- Receives the datetime-formatted string

- Parses it into a

Dateobject - Creates a default localized string from the object

- Returns the localized string

Turns out this is not going to be exactly what we need. The time zone, which is critical for our solution, is missing. We’ll use it as a placeholder, though, and improve it later.

Using a regular expression to find datetimes

Since our back-end dev did not identify the date stamps with mark-up, we’re going to be scanning text for a datetime pattern. Scanning text for patterns can be a problem because the text we’re hoping to match comes mixed among an enormous variety of words and character constructions. Some people, when confronted with such a problem, think “I know, I’ll use regular expressions.”2 Which is exactly what we’re going to do:

const iso8601 = new RegExp(/(\d{4}-\d{2}-\d{2}[:.T\d]*Z)/);

This regular expression matches text that is

- Four digits, followed by

- A hyphen, followed by

- Two digits, followed by

- A hyphen, followed by

- Two digits, followed by

- Any number of any of the following characters in any order

- A colon

- A decimal point

- A capital ‘T’

- Any digit zero through 9

- Followed ultimately by a capital ‘Z’

The regular expression also uses parentheses—just inside the forward slashes that delineate the regular expression—to create a capture group. This capture group turns out to be essential for our purpose: Its utility will become clear later on.

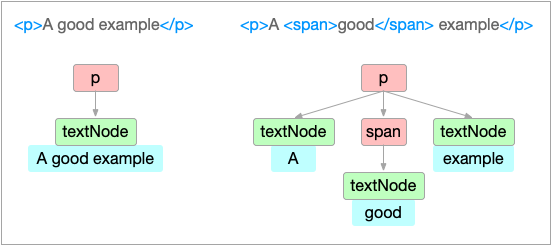

Find on page? It’s not that simple

The document object model, which front-end devs use to explore and change HTML pages, gives good access to

- HTML elements

- HTML element attributes

- HTML element text content

The DOM, though, does not have tools to identify a phrase of text from

within an element, nor, naturally, does it provide tools to replace that

phrase with an element, such as—to our purpose—a span element.

The go-to function for locating page content, querySelectorAll, does

not have a polymorph that accepts our regular expression, or anything of

the sort. We’ll need a different solution.

Our driver function

Returning to our localizeIsoStrings(event) function, we know that we

aren’t going to do anything with the event object passed. The

JavaScript convention for identifying parameters that you

receive, but that you are not going to use, is to prepend it with an

underscore:

function localizeIsoStrings(_event) {

}

Our strategy will be to visit each node in the DOM looking for text,

and, when text is found, scanning the text for the phrase we’re looking

for. Once found, we’ll create new text, wrap the new text into a span

element, and then replace the found text with our created span element.

The DOM is a tree structure of nodes. The process of visiting each node

is known as walking the DOM. Turns out, most browsers support a

function called TreeWalker for doing this. Unfortunately, although

TreeWalker makes it easy to retrieve content from various places in

your page, it doesn’t have good support for changing those pieces when

you find them. So we’ll roll our own walker.

Walking the DOM

The typical pattern for visiting nodes in this fashion is to start with one node, get a list of its children, and then process each child in turn. If any child has children of its own, recurse into that child and so on till you run out of children.

Because we’re going to recurse, our localizeIsoStrings function will

merely start the walk by identifying the node to start from and the

pattern to search for. We’ll insert our regular expression outside our

recursion so we don’t waste time and memory creating and destroying

objects with each iteration.

function nodeWalker(node, re) {

}

function localizeIsoStrings(_event) {

const iso8601 = new RegExp(/(\d{4}-\d{2}-\d{2}[-:.T\d]*Z)/);

nodeWalker(document.body, iso8601);

}

Add the first guard clause, start the loop

Since we’re looking for text nodes only, and since text nodes never have child nodes, we can skip childless nodes: No text there. Then we’ll start our loop:

function nodeWalker(node, re) {

if (!node.hasChildNodes()) return;

for (const child of node.childNodes) {

}

}

Add guard clauses in the loop

Within our loop, we want to start another iteration if the child is an element node, which might contain text, and then shortcut the loop if the current node is, itself, not a text node and therefore not interesting to us. Add two guard clauses:

function nodeWalker(node, re) {

if (!node.hasChildNodes()) return;

for (const child of node.childNodes) {

if (child.nodeType === Node.ELEMENT_NODE) nodeWalker(child, re);

if (child.nodeType !== Node.TEXT_NODE) continue;

}

}

Process text nodes

At this point, we know our current child node is a text node. If it

wasn’t, we’d have left the loop. So let’s get the text content of the

text node from its textContent property:

child.textContent

String.split()

Now we’ll split the string into an array of strings. We’ll split the

string on the pattern of the datetime string we’re looking for. The

JavaScript split method takes either a string or a regular expression.

In typical use, these separators are discarded:

"Fly, you fools!".split("/\s+/");

⬅︎ ▶︎ Array(3) [ "Fly,", "you", "fools!" ]

Note how in the above split, the space characters are gone. None of the strings in the array contain spaces, and if we join the array of strings back into a single string, it looks wrong:

["Fly,", "you", "fools!"].join("");

⬅︎ "Fly,youfools!"

However, if you include a capture group in your regular expression by including parentheses, the split function splits the string at the beginnings and ends of the group and inserts the match between:

"Fly, you fools!".split("/(\s+)/");

⬅︎ ▶︎ Array(5) [ "Fly,", " ", "you", " ", "fools!" ]

As you remember, we wrapped our regular expression for matching datetimes within parentheses so when we split on it, we get an array of strings, with zero or more of the strings in the array exactly matching our datetime pattern.

Process each segment in the split string

The next step is to use the map method (of big data map/reduce fame)

to evaluate each element in the array. If the string matches our

datetime pattern, then replace it with our replacement span element,

else convert the string back into a text node. Now we have an array of

nodes: zero or more are text nodes, and zero or more are span element

nodes.

Remove zero length text nodes

A final optimization: Filter the resulting array to remove any text nodes where the length of the represented string is zero characters long. The zero-length nodes won’t be visible on the web page, but there is no point is adding meaningless nodes to the DOM for the browser to keep track of.

"123".split("/(\d+)/");

⬅︎ ▶︎ Array(3) [ "", "123", "" ]

The nodes array

We’re going to work all that whole logic into one step and call the resulting array of nodes, “nodes”:

function nodeWalker(node, re) {

if (!node.hasChildNodes()) return;

for (const child of node.childNodes) {

if (child.nodeType === Node.ELEMENT_NODE) nodeWalker(child, re);

if (child.nodeType !== Node.TEXT_NODE) continue;

const nodes = child.textContent

.split(re)

.map((segment) => {

return re.test(segment)

? wrapIsoString(segment, localIso8601String)

: document.createTextNode(segment);

})

.filter((i) => i.textContent.length > 0);

}

}

Create a document fragment to contain our nodes

Now we just have to replace the current node with the nodes stored in

our “nodes” array. The replaceWith method does not accept an array of

nodes, but it does accept a document fragment object. So, we’ll create a

document fragment, populate it with the nodes, and then replace our text

node child with the resulting object:

function nodeWalker(node, re) {

if (!node.hasChildNodes()) return;

for (const child of node.childNodes) {

if (child.nodeType === Node.ELEMENT_NODE) nodeWalker(child, re);

if (child.nodeType !== Node.TEXT_NODE) continue;

const nodes = child.textContent

.split(re)

.map((segment) => {

return re.test(segment)

? wrapIsoString(segment, localDateString)

: document.createTextNode(segment);

})

.filter((i) => i.textContent.length > 0);

const df = new DocumentFragment();

nodes.forEach((i) => df.append(i));

child.replaceWith(df);

}

}

Note that the the “true” fork of the map lambda calls the

wrapIsoString function that we wrote earlier. Also note that the

wrapIsoString function takes two parameters: an isoString and a

transformer function. The transformer function we’re calling here is

the one we wrote earlier called localDateString.

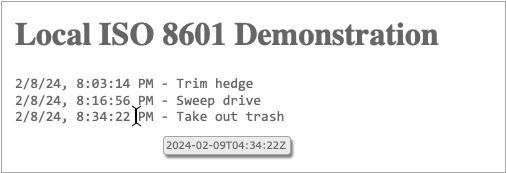

Our first run

At this point, our implementation should be functional. Let’s try it out:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en-US">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<title>Local ISO 8601 Demonstration</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Local ISO 8601 Demonstration</h1>

<pre>

2024-02-08T20:03:14Z - Trim hedge

2024-02-08T20:16:56Z - Sweep drive

2024-02-08T20:34:22Z - Take out trash

</pre>

<script src="script.js"></script>

</body>

</html>

As expected, localized time stamps with the mouse-over pop-up are working,

but time zones are not displayed. So we’ll return to our localDateString

transformer function.

Search MDN for “format date”

We’ll search the docs for an API dedicated to formatting dates,

“format date”,

and locate Intl.DateTimeFormat. The example in the docs is basically

this, which looks promising:

new Intl.DateTimeFormat("en-GB", {

dateStyle: "full",

timeStyle: "long",

timeZone: "Australia/Sydney",

}).format(new Date());

⬅︎ "Tuesday, 20 February 2024 at 13:11:31 GMT+11"

A close reading of the docs, trial and error at the console, and a bit

of Googling gets us the proper option values, and a call to replace

removes the “at”:

new Intl.DateTimeFormat(navigator.language, {

dateStyle: "medium",

timeStyle: "long",

}).format(new Date("2024-02-08T20:03:14Z"))

.replace("\x20at", "");

⬅︎ "Feb 8, 2024 12:03:14 PM PST"

As before, we’ll wrap this in a function so we can reference it in our program:

function localDateString(dateTime) {

return Intl.DateTimeFormat(navigator.language, {

dateStyle: "medium",

timeStyle: "long",

}).format(new Date(dateTime))

.replace("\x20at", "");

}

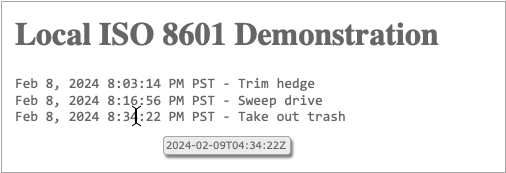

Our second run

Success! The HTML is delivered one way for every reader, and each reader’s browser formats the dates according to the reader’s own locale. Done.

And the back-end dev is still muttering about logins, user profiles, locale preferences, databases, front-end bloat, and how it would therefore be easier to simply deliver the desired date formats right in the HTML specifically as the user wants it with every request. Uh-huh.

🐉

-

Misha Wolf and Charles Wicksteed, “Date and Time Formats”, W3C Note. Sept. 15 1997. ↩

-

Jamie Zawinski, Usenet posting in alt.religion.emacs Aug. 12, 1997. Via Jeffrey Friedl, “Source of the famous ‘Now you have two problems’ quote”, Jeffrey Friedl’s Blog, Sept. 15, 2006. ↩